Introducing the hunter gatherers (and the crazy anthropologists who study them), Part 1

In which we meet Richard Lee and the !Kung

I’ve been writing and talking about “the hunter-gatherers” for a long time without a proper introduction. Who the heck are these people anyway and why are we so interested in them? How do we know what we know about them? Who are the folks crazy enough to venture out into the most isolated patches of desert and rainforest to study them? Buckle your seatbelts: this is a long one, but I’ve tried to make it as entertaining as possible. Since the human attention span for reading is undeniably short these days (mine included), I’ve divided it into 3 parts. This is the first.

The Golden Age of hunter-gatherer research started on October 7, 1963 when a man named Richard Lee, a graduate student in anthropology from the University of California Berkeley, set out across the Kalahari desert in a Land Rover with a local government official, traveling eight hours through 100 kilometers of acacia forest and desert terrain, with no water or people in sight. After hours of driving through sand, stopping intermittently to dig out the car, they arrived in what is now known as the Dobe area where a small group of !Kung were camped out. The !Kung (or Juǀʼhoansi as they are sometimes called) are one group of San bushpeople who live in what is now Botswana and Namibia. Those exclamation points and apostrophes represent different kinds of click sounds. The !Kung speak a complex click language that is famously difficult to learn (although quite a few dedicated anthropologists managed it) and is thought to be very ancient. In fact, some linguists believe that all humans spoke click languages at one time, and that non-click languages simply lost the click.

Lee, originally a primatology student who found that studying monkeys just wasn’t his thing, was looking for a better way of understanding humanity’s evolutionary origins. He was tipped off to the existence of the !Kung by Professor Desmund Clark, who had recently joined the Berkeley faculty after decades of research work at the Rhodes-Livingstone Museum of Zambia. Lee floated the idea of studying the !Kung for his graduate thesis with his advisor Irven Devore, then at Harvard, who was wildly enthusiastic. Both were in their twenties. Together they managed to raise a bunch of grant money, flew to Botswana and got their hands on a Land Rover. The !Kung were so remote that after months of combing the Kalahari desert in search of them, they had to concede defeat. DeVore returned to the United States but Lee, still an eager-beaver grad student without any pressing commitments back home, continued the search alone. Through a series of introductions, he eventually made contact with a man named Isak, headman of the !Kangwa district, who spoke no English but was fluent in both Setswana and the !Kung click language. Isak knew of the !Kung and knew where to find them, but insisted on interviewing Lee for seven hours before agreeing to lead him to their camp (a kind of gatekeeping for which I have the highest admiration and a protection I can only wish all hunter-gatherer societies had).

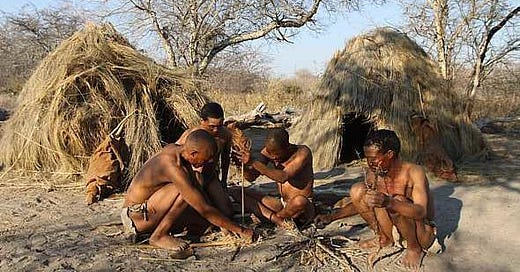

And so it was that on October 7, 1963, Lee found himself in the Dobe area of the Kalahari desert, about 400 kilometers away from the nearest phone, doctor, or car repair garage. Isak introduced Lee to the !Kung, saying Lee had come to live there and learn their language, and in exchange he would give them tobacco. Lee ended up living with them continuously for two and a half years, at times in near-total immersion, eating their diet and sleeping in the grass huts. As he puts it in his book, The !Kung San, “I came to have a healthy appreciation for the cheerfulness and effortlessness with which they faced a way of life that was for me quite uncomfortable.” I would argue that ‘uncomfortable” in this context is a euphemism. I have read enough about the !Kung at this point to understand that this probably entailed eating quite a lot of bugs (caterpillars are a favorite), tubers so chewy that you have to spit out large clumps of indigestible fiber after having sucked out the nutrients, and every imaginable part of an animal (including skin, brains, eyes, and other organs). There are no beds and no bedding. Everyone sleeps on the ground inside a temporary grass hut and they keep a fire going at the entrance for warmth (which means you have to wake up often throughout the night to stoke it). Water is so scarce in the dry season that the only source of hydration comes from squeezing a drizzle out of the underground bulbs they dig or - and I am dead serious about this - drinking the digestive juices out of the rumen of a freshly-killed antelope. To put it mildly, living with the !Kung is hardcore and Lee was a dedicated researcher.

Despite the rigors of life in the bush, the only thing that really seemed to bother Lee was dealing with the Land Rover. In his book, The !Kung San, he describes how, “It was 40 kilometers [from where I was camped] to the main camp at Dobe [and] over 350 kilometers to Maun. These were trips one did not undertake lightly. Driving in the Kalahari desert extracts a tremendous toll on motor vehicles…A breakdown in the dry season might mean a 40-kilometer walk to the nearest water point. In the rainy season, it could take two days to dig out of the mud. In three years of fieldwork I suffered through mechanical breakdowns without number and performed repairs I would never think of attempting anywhere else. I grew to thoroughly dislike the vehicles we drove and paradoxically to be moved to tears of thankfulness whenever one of them actually functioned for 100 kilometers at a stretch.” The !Kung, on the other hand, absolutely loved the Land Rovers. Here’s a song they apparently sang when they got to ride in one:

“While the truck does the work, we sit around and get fat

Those who work for a living; That’s their problem!”

Seriously, I love these people.

Lee was also the first English-speaker to ever learn the !Kung click language. When he first established camp he needed two interpreters to understand anything the !Kung said: one to translate from !Kung to Setswana and another from Setswana to English. In his own words, “the answer came back like a broken telephone,” but by the end of his second year there he was fluent in click-speak.

In 1965, Lee returned to Cambridge and finished work on his thesis. The following year, in 1966, he and Irven Devore organized a famous conference called Man The Hunter that brought together all of the leading hunter-gatherer anthropologists of the time (or at least, leading American ones). To this day, many believe that conference was one of the high-points of evolutionary anthropology. It kicked off a massive interest in hunter-gatherer societies as a means of better understanding our shared evolutionary past. An entire new field was born, known as ethnoarchaeology, the practice of using ethnographic research with contemporary hunter-gatherers in order to interpret archeological findings. The conference also kicked off a massive wave of interest in the !Kung. From the period between 1967 and 1980, a flood of researchers visited the Dobe area to study every aspect of the !Kung’s lives. They included James Woodburn, a British sociologist who has been studying the Hadza of Tanzania, and whose story we will come to shortly, as well as Melvin Konner and his wife, Marjorie Shostack, whose intensive research on !Kung childhoods and the lives of women and mothers forms the backbone of this book.

The !Kung became so famous that anthropologists who have built their careers studying other hunter-gatherer societies have lamentingly referred to them as the “poster child” for the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Part of the reason that anthropologists became so obsessed with them is that they seem to be good candidates for representing our shared African evolutionary past. When they were first contacted by Lee in 1963, most were still living as true hunter-gatherers, with no dependence on wage-labor or trade with agricultural neighbors: an extremely rare phenomenon, even for the most remote groups. Studies of San DNA suggest that they began to diverge from other human populations in Africa as early as 200,000 years ago and were fully isolated by 100,000 years ago. Although they have had various forms of contact with outsiders over the years, as late as the 1960s and 70s the !Kung were living as they had been for literally hundreds of thousands of years. They are also famously egalitarian, communal, loving, and not-so-hard-working (not because they are lazy, but because the land provided them with everything they needed in exchange for a few days of hard work per week and working too hard in scorching desert conditions with scarce water will literally kill you). Following the Man The Hunter conference, the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins famously called them “the original affluent people” because they spent so much time in leisure. Whether or not it’s true, we would all like to believe that life in our deep evolutionary past resembled that of the !Kung: peaceful, loving, egalitarian, and relatively chill.

Side note: the !Kung were so famous that the 1980 blockbuster film The Gods Must Be Crazy was inspired by them. This film is problematic on so many levels it would take a whole book to elucidate them. It’s racist, sexist, implicitly pro-apartheid and ridiculously diminutive and patronizing in its portrayal of the San bushmen (they are repeatedly referred to as “the sweetest little buggers” and portrayed as being exceedingly ignorant. The narrator goes so far as to suggest that they do not know what a rock is, as if they hadn’t been using stone tools for millenia). Nevertheless, if you are interested in seeing what San people look like, what their click language sounds like, and what their physical environment is like (a lot of the movie is filmed in the Kalahari desert) then I recommend watching the first fifteen minutes. Even better, look up some of the original documentaries on the !Kung made by filmmaker John Marshall in the 1950s. The footage is truly extraordinary and offers a window into what their lives were like before the loss of their ancestral lands.

Today, the !Kung mostly live on reservations established by the governments of Namibia and Botswana. Lack of ownership rights to their ancestral lands meant that cattle ranchers were free to encroach on their hunting grounds, polluting the water with animal droppings and trampling the sparse vegetation that both the !Kung and the animals they hunted depended on. White settlers have actively encouraged the !Kung’s participation in wage labor and many young men have been recruited for military service. Inequitable access to wage labor has increased women’s dependence on men for food, leading to growing gender inequality and higher instances of domestic violence. Their famous egalitarianism has also crumbled as people hoard cash and crops. Many have died of tuberculosis, a disease to which they have virtually no immunity. It’s a tragic outcome for such a proud, independent people and one that has sadly been repeated many times throughout history.

By 1970, around the time that Konner and Shostack were wrapping up their research with the !Kung, Irven DeVore, the same Harvard anthropologist who had helped to kick off the whole !Kung obsession, was starting a new project with a new hunter-gatherer society: the Efe of the Ituri rainforest in The Democratic Republic of Congo…

But to learn about the Efe and other hunter-gatherers of the Congo, you will have to wait until next week!

Thank you so much for summarizing all this for us. While I daydream about being born 15,000 years ago, I am least grateful that today we have some understanding and knowledge of how we used to be (thanks to these anthropologists). It helps me feel less crazy and depressed. Living in the early 1950s and having no concept of WHY things felt so weird and inequitable - I feel for those mothers.

Really interesting read! Especially that the Aka men suckle their babies for comfort. Your Substack and Instagram have been so informative and helpful in me understanding but couldn’t articulate why I sometimes feel so fucked off with everything motherhood—because we’re not mean to do it like this!

I’m in Australia, which seems to be lot better than America but we’ve still got a long way to go too.

One small point for thought—the word “aborigine” is considered outdated and offensive with colonial connotations by many Indigenous Australians and Australians. More accepted wording is to use their specific clan name if you know it, Indigenous Australians, First Nations people/s (plural as there were originally 200+ different tribes of people), Aboriginal Australians or Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander people if you’re including Torres Straight Islands as well.