What does feminism mean to me?

In the aftermath of the election, we need to examine our definition

There has been a lot of discussion lately about women and men, about feminism and toxic masculinity, and about whose job it is to fix it. There is a lot of focus on how men feel alienated by certain kinds of feminism and a lot of attention being given to versions of feminism that emphasize women’s total self-sufficiency (such as the Korean 4B movement advocating for no heterosexual sex, dating, marriage and no children - which has been getting quite a lot of press coverage of late).

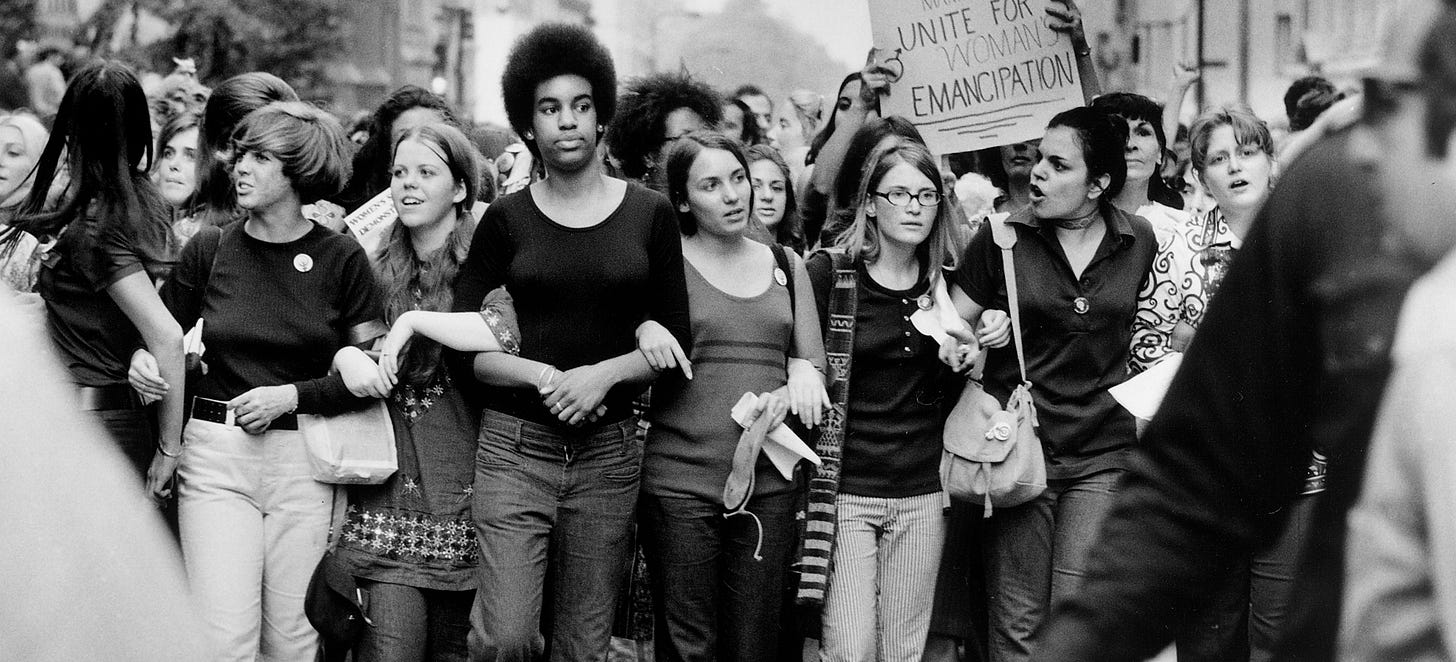

Because there is a lot of confusion about feminism right now, I think it’s worth briefly reviewing the history of the movement before we delve into what it means in the contemporary context. The first wave of feminism, beginning in the late 19th century, focused mainly on women’s suffrage. The second wave began in the 1960s and called for a reevaluation of traditional gender roles (especially women’s confinement to the role of wife and mother) and for the end of sexist discrimination. Second-wave feminists secured the passage of the Equal Pay Act and reproductive freedom under Roe v. Wade (which was then overturned in 2022). Third wave feminism emerged in the 1990s and focused more on issues related to sexual harassment and lack of women in positions of power. This wave of feminism sought more inclusivity with regards to both race and gender (what is now known as “intersectional” feminism). Most experts agree we are currently in the fourth wave of feminism, which continues the work of the third wave, and is intimately related to the #MeToo movement and holding men in power accountable for their actions. Many fourth-wave feminists are dedicated to examining and critiquing the systems that allow such abuses of power to occur.

All of these waves were necessary and, on the whole, I believe they have benefitted women and society in general. However, I also feel that the work of feminism is unfinished and that certain kinds of feminism may inadvertently do more harm than good to society as a whole. I believe I am allowed to call myself a feminist and also critique feminism. I believe feminism is a work in progress and I see myself as being part of that work.

Since becoming a mother, I have struggled with feminism and what feminism means to me. The version of feminism I subscribed to before children (something closely akin to Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In philosophy) no longer serves me. That’s not to say that Sandberg’s feminism is not necessary or valid. It just doesn’t speak to me in this phase of my life, as a mother of two young children.

Andrea O’Reilly has written extensively about the failure of feminism to include discussions of motherhood and empowered mothering practices. Because second-wave feminism was focused on liberating mothers from the confines of domesticity, many feminists (both then and now) seek to distance themselves from motherhood. Thinkers like Julie Stephens have pointed to a phenomenon called “post-maternal thinking” and the desire of feminism to erase maternalism from contemporary society.

I agree with much of O’Reilly and Stephens’ thinking on feminism and motherhood, but I also feel that both fail to deliver a concrete vision of a new feminism that is both respectful of the necessary prior waves of feminism, while also acknowledging and including the importance of motherhood in feminism. Their work focuses more on critiquing issues with existing versions of feminism (which is necessary) but I always feel myself wanting more (wanting a solution?).

These days, in social media and the newsletters I follow, I hear a lot of women talking about how contemporary feminism should be about “choice.” This is mainly a way of dealing with the thorny question of motherhood. Under the choice framework, women can choose to be stay-at-home mothers and that is an empowered decision, just as the choice to go to work is an empowered decision. The “choice” framework was used to defend Hannah Neelemen from criticism after the viral article was published about her life as a Mormon mother of eight and “trad wife” social media influencer. If Hannah Neeleman says she is happy in her life, then who are we to judge her? They make a good point.

I wrote a critique of this “choice” framework in an earlier post, on the basis that choice is not as free as most people make it out to be. A woman's “choices” in Mormon society are limited, both by the people around her as well as her own internalized notions of what is “good” and acceptable for a woman. In that piece, I advocated for a return to the original definition of feminism as being about equality between the sexes. But no sooner had I published that piece than I ran into another tricky intellectual question: how can we advocate for equality between the sexes when, biologically-speaking, things are not equal? Which is to say, especially when it comes to motherhood, women bear the brunt of things. Women (and anyone with XX biology who identifies differently) are the ones that birth and breastfeed. To ignore this is to ignore the fact that mothers require different accommodations (in the workplace, for instance) in order for the race to be fair. Equality and equity are different. Equality is the idea that everyone should be treated the same, while equity is the idea that people should be given the resources they need to be successful. If equity is the end-game (as I think it should be) then we need to acknowledge the biological differences between cisgender men and women (and between people who birth and breastfeed and those who do not) in order to create a just society. So depending on what is meant by “gender equality,” I suppose I don’t quite line up with the traditional definition of feminism either.

My favorite definition of feminism is one that I found while reading bell hooks. She says, “to be ‘feminist’ in any authentic sense of the term is to want for all people, female and male, liberation from sexist role patterns, domination, and oppression.” She also emphasizes the importance of community and of love, both within and beyond the confines of romantic love and the nuclear family. This gels perfectly with my own research on hunter-gatherers, our evolutionary origins as a species, and what the research has to say about human flourishing. We thrive when we love and depend on one another. This is not about women versus men. This is not about self-sufficiency and independence. It is about love and interdependence and wanting a better world for everyone.

After hours of late-night and early-morning reflection (the only time I get to think is when my kids are asleep) I have decided that my own definition is not far from hooks’, but with a bit of a tweak. To me, feminism means wanting health and flourishing for ALL people and recognizing that patriarchal systems and institutions prevent that in objective, quantifiable ways. For example, patriarchal systems that isolate mothers from extended communities of help and support hurt mothers in ways that we can objectively measure. By hurting mothers, we hurt children of all genders and we cause collective trauma, to be repeated in the next generation.

What I believe we are witnessing in this era of darkness and polarization is an escalation in fear and anxiety related to the crushing economic oppression of our late-stage capitalist (and patriarchal) system. That fear and anxiety is causing women and men to turn against one another, when what we need is to come together to fix our broken system.

Yes! Love your point that we all need each other. Extreme independence can be tempting compared to all the emotional work required to tackle the subconscious sexism in ourselves and our relationships... But if we don't do it, who will? Its not fair but life never is and if we want a better world we have to work to create it.

I especially agree with the conclusions. Feminism, during my life as a young adult, was divisive. The main issue now, as I see it, is to dissolve the polarities but to have "equity" for all.