It’s Black Friday today. Not so long ago, I used to count the days until it arrived. I had all of my purchases already planned. Mostly clothes. Mostly for me. The second I got the discount code in my inbox I would go into a purchasing frenzy. This made me happy…temporarily. Mostly I liked buying. I also liked opening the packages after they arrived. Beyond that, owning more clothes typically gave me very little pleasure. It’s not that I don’t appreciate nice clothes (I am especially addicted to secondhand luxury shopping and finding “deals” on quality items), it’s just that I am already wayyyyyyyyyy over on the right-hand side of the diminishing marginal utility curve. In other words, I already have more nice things than I can possibly wear or appreciate.

Shopping is addictive, just like alcohol and gambling, but we don’t think of it that way. We think of overconsumption as a personal choice: yet another moral failing to add to our roster. Never before has it been so easy to buy, or be advertised to. My own addiction started with the rise of social media and online shopping (which, unfortunately for me, coincided with the period in my life when I actually started earning decent money). I saw items on influencers or in ads on Instagram that I just had to have. That would kick off a cycle of shopping for lookalikes on second-hand sites (something I could easily do from home, even after becoming a mom, while my baby slept on my chest). When I found something I wanted, I didn’t even have to get up to enter my credit card. Paypal had that covered for me in one click. If I had the fortitude to resist a purchase (which I found hard in the addled postpartum period when I was both woefully lacking in willpower and also feeling that I deserved something from the world in exchange for my struggles) it would come back to haunt me. I would be casually considering a new soup recipe and there it would be, that beautiful pink cashmere sweater that I had recently abandoned, right between the ingredients and the baking instructions, beckoning me.

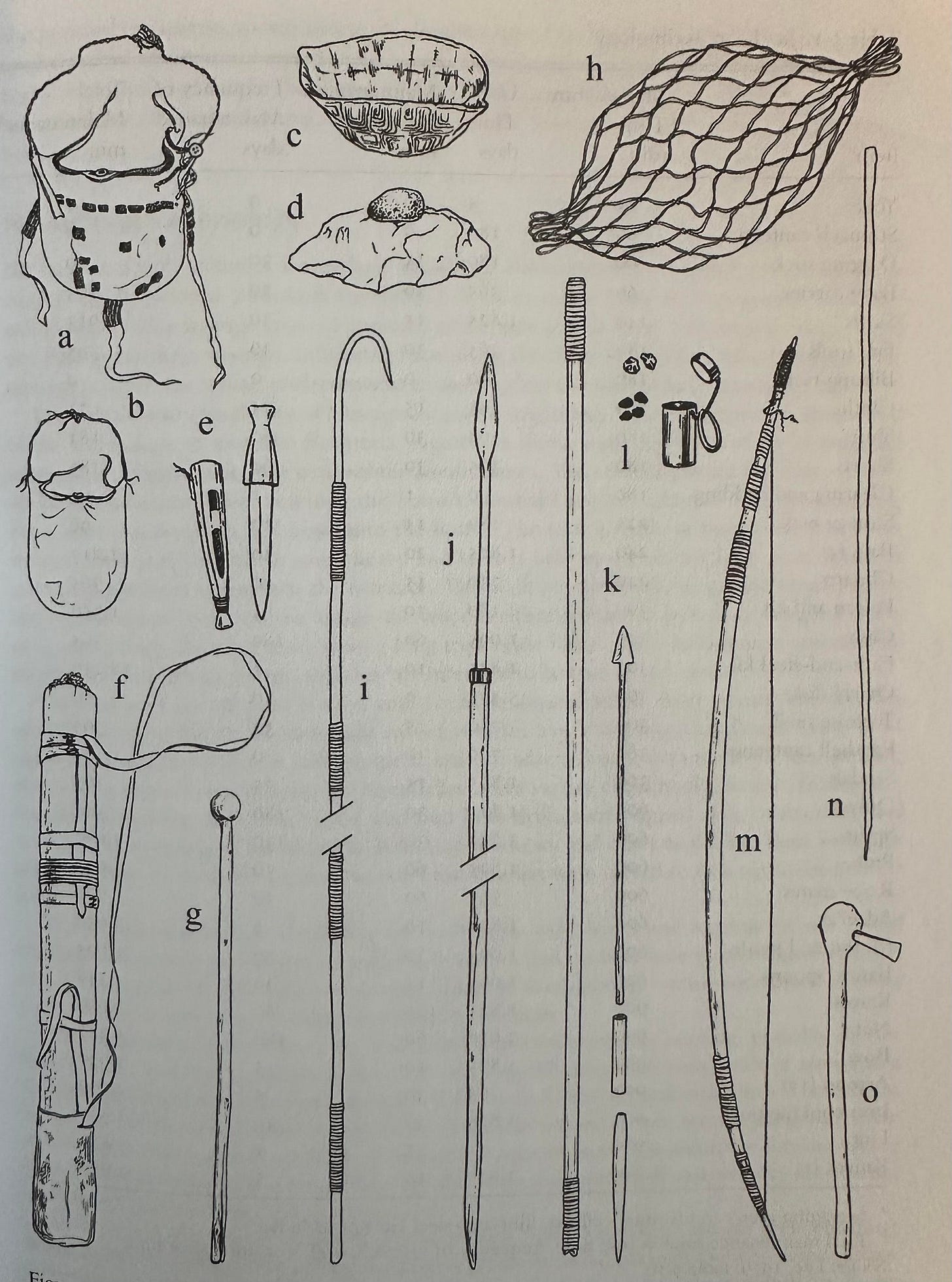

!Kung technology: a complete inventory

For most of human history, people had only as many possessions as they could carry. Humans lived as hunter-gatherers for 95% of our existence as a species and hunter-gatherers are nomadic. They set up camp in a region and stay until they have exhausted the food resources locally; then they move. How often they move depends on the society, the season, and the distribution of resources, but most move often. The !Kung move about six times per year, and in some seasons as often as every three weeks. The Aka and the Hadza are similar. The Agta move 20 times per year! Every time they move, they must walk for up to 15 miles, sometimes in extreme heat, to get to their destination. Babies and small children must also be carried. As such, the number of possessions one can own is severely curtailed by the constraints of this nomadic lifestyle.

Furthermore, most tools can be made from natural elements found in the local environment, so they can easily be left behind and remade. When a group relocates, they will rebuild their homes from grasses, branches, and leaves in a couple of hours. They will find new stones for pounding nuts. They will find new branches from which to fashion digging sticks. The only items worth carrying are the ones that require considerable effort to remake and that are light enough to be moved. Again, this list varies from society to society, but here is a typical inventory of what a hunter-gatherer mother might carry with her on a move, based on Frank Marlowe’s ethnography of the Hadza:

Digging sticks: this is a woman’s most important tool, since digging tubers is a major part of women’s foraging work. These sticks are fashioned from found branches and sharpened using a knife. They are extremely lightweight and easy to carry, but are also easy to make, so a woman may or may not bring hers on a longer move.

Knives: these cannot be made from found objects and so they are always carried, but they are typically small and light.

Gourds and baskets: these are very valuable tools for carrying water, honey, and coals and storing fat. Because they are so essential and take time to make, these are typically carried.

Skins and clothes: these are also considered essential and valuable and so are always taken from camp to camp, though usually they are simply worn (and rarely changed). Men, women, and children all wear many decorative beads because they are beautiful and easy to transport.

Infant slings: apart from the digging stick, this is a woman’s most important tool in hunter-gatherer society. Infants under age two are carried everywhere and without the sling, mothers would have a hard time working while concomitantly caring for babies.

Infants and young children: while not exactly “tools,” they still had to be carried, and boy are they heavy!

That’s it. Men carry bows and arrows, tools for making fire, axes and knives, as well as many of the same things the women carry. No one is particularly possessive of any of these items. In fact, the concept of private property is virtually nonexistent. If someone in camp needs a tool to do something and one is available, they will take it and use it. It doesn’t matter who “owns” that tool.

You might be thinking: Who cares? We don’t live as hunter-gatherers anymore. We don’t need to be that minimalist. What’s the benefit?

I am not advocating for extreme minimalism, a la hunter-gatherer. However, comparative studies of Westerners and hunter-gatherers often find that hunter-gatherers are happier. In one study, Hadza hunter-gatherers scored an average of 1.28 points higher than Polish respondents on a 7-point Likert scale of Subjective Happiness. That’s 18% better. The average Hadza score was 5.83, which is significantly higher than the average in all industrialized societies, and pretty darn close to perfect (if 7 is the best score). These studies are limited and fraught with methodological concerns, since there are massive cultural differences between these societies that affect responses, but it echoes what most hunter-gatherer anthropologists report, which is that these people seem pretty cheerful on average, despite the extremely uncomfortable lives they lead.

If hunter-gatherers are happier than Westerners on average, and they have virtually no personal possessions, then I think it’s safe to say that owning more stuff is not the answer. We think we will be happy if we can only have that thing we so desperately want, but when we get it, it rarely moves the needle. Instead, we erode our hard-earned savings (or worse, go into debt) all while burning the planet to the ground in the name of capitalism.

Worse, there is some evidence to suggest that owning more stuff might actually make us unhappy, especially mothers. When we become parents, our homes suddenly explode with stuff. We think we need all of this stuff because it will make our lives easier. We think that if we invest in a good baby swing then that will help keep our baby calm so we can get more work done. We think that if we buy a Snoo we will get more sleep at night. We think if we buy a jogging stroller then maybe we will actually go for a run with our baby. We think if we buy 24 baby onesies then we won’t have to do the laundry every three days. We think if we buy our children more toys they will be more easily able to entertain themselves and that will free us up for more work and rest. What we actually need is community, and since we don’t have it, we are trying to buy our way out of the struggle and exhaustion of parenting alone.

It’s true that many of these things can be helpful in the short-term, but in the long-term they end up adding clutter, complexity and chaos to our lives. And who is left to clean up the mess? You guessed it: mom. In a fascinating study of 32 middle-class, dual-income families in Los Angeles, a group of researchers from the UCLA Center on Everyday Lives of Families (CELF) used an ethnoarchaeological approach to better understand how people in the modern context interact with their material culture. Their research culminated in a book, Life at Home in the Twenty First Century, and a TV mini-series called, “A Cluttered Life: Middle Class Abundance.” They discovered that contemporary US households have more possessions than any society in global history and that this proclivity for hyper-consumerism has resulted in mountains of stuff accumulating in every corner of the household. This will come as no shock to anyone who has watched an episode of Marie Kondo’s Netflix Series or the popular show Hoarders, but the researchers had an important additional finding: the management of all of this clutter is gendered. According to researchers Elinor Ochs and Jeanne Arnold, “it’s clear [that all of the stuff] was creating some significant stress for these families, particularly the mothers. The finding was that women who looked around their homes, and remarked on the clutter, and remarked on the effect of the clutter on their lives [said] that it was an ever-present, ongoing burden for them to manage…When we looked at the cortisol levels of those women, their cortisol was very high.” On the other hand, the researchers found that “men generally did not even remark on the clutter.” They conclude that, “there’s a greater tendency to remark on the clutter if it bothers you, and if you’re the one who is responsible for tidying it up.” Unfortunately, despite the fact that in all families studied, both the mother and the father worked outside the home, the mothers were the ones who felt responsible for managing the clutter and who felt the stress of it.

So add this to your roster of feminist mantras: fuck stuff.

Reading mountains of literature on hunter-gatherers really challenged my thinking on what is essential in life. Because hunter-gatherers are so extreme in their minimalism, they force us to think hard about what a human being really needs to feel satisfied. Afterall, if humans survived and thrived for hundreds of thousands of years with almost no material possessions, then perhaps we have all totally lost touch with what we actually need.

Most books on “minimalism” focus on decluttering and organizing what we already have, rather than on how to stop the toxic cycle of buying and decluttering. The thing that helped me the most, apart from immersing myself in the hunter-gatherer literature, was Anna Lembke’s book, Dopamine Nation. That book helped me realize that my shopping habit was an addiction just like any other, and when I started treating it that way, I was able to solve it. I canceled all of my credit cards. I wired my savings into an investment portfolio that I made deliberately difficult to access and left only enough money in my checking account for essentials. I learned to avoid triggering situations. I unfollowed hundreds of style influencers and learned to quickly scroll past content aimed at selling me things I don’t need. I deleted all of my shopping apps. I bought physical recipe books so I wouldn’t have to look at ads while looking up chocolate chip cookie baking times. It worked. I still buy clothes, but only occasionally, and only if I feel that the purchase will really solve a problem or enhance my life in some way.

Not everyone needs to be as extreme as I was. Not everyone who goes on a Black Friday spending spree has an addiction. Not every purchase is bad. Some things really do enhance our lives in meaningful ways. I am not trying to tell you how to live your life. We’ve got enough of that. I am simply sharing my story about how learning to control my spending really made me feel better, in case it can help you or someone you know.

If you do want to spoil yourself over the holidays, or get a meaningful gift for someone you love, I suggest buying an experience, especially if it's social. Social experiences do make us measurably more happy, unlike physical objects. So consider gifting a voucher to a favorite restaurant, community cafe, or spa. (If you’re in the San Francisco area, I just had a wonderful afternoon at the Alchemy Springs social sauna with friends). Take your parents out for a meal. Use the money you would have spent on sweaters to hire a babysitter and go to a cafe and read a book in peace. Instead of buying your kids more plastic dinosaurs, buy them a season pass to the local natural history museum where they can see a real dino skeleton (or make the grandparents buy the pass for them AND take them there the next time they visit, while you go to that cafe with your book). You get the gist.

But if you do end up with 200 new plastic toys come Christmas, don’t blame yourself. That’s just the society we live in. Do, however, consider teaching your kids (and your husband) how to put them back in the basket when they are done.

"What we actually need is community, and since we don’t have it, we are trying to buy our way out of the struggle and exhaustion" I'm not a mother, but funnily enough that sums up my Black Friday purchases exactly.

I don’t know. I like the idea of not buying things in theory, but in practice, I find it doesn’t really work. I love reading, so I buy a lot of books. I love crafts, so I have a lot of craft supplies. I love gardening, so I buy a lot of plants and seeds. I love to cook and entertain, so I must have dishes, cookware and serving utensils. I want to support small businesses and artisans who make pottery serving pieces with which I can entertain, clothes I can wear, pictures to hang on my wall, etc. The list goes on. I think deep down I am just a maximalist because I want to live a full and beautiful life. Yes I stress about clutter occasionally but I think people also stress out too much about decluttering, or they think it’s going to solve a spiritual problem for them.