Introducing the hunter gatherers (and the crazy anthropologists who study them), Part 2

In which we meet the Efe, the Aka and the Hadza

This is part 2 of a 3-part series designed to introduce people to the hunter-gatherer groups I refer to most often, and the anthropologists who did the research. If you missed Part 1, I suggest going back and reading that first! You might want to get a cup of tea: this one’s a bit long (but interesting I promise!).

By 1970, around the time that Konner and Shostack were wrapping up their research with the !Kung, Irven DeVore, the same Harvard anthropologist who had helped to kick off the whole !Kung obsession, was starting a new project with a new hunter-gatherer society: the Efe of the Ituri rainforest in The Democratic Republic of Congo. It became known as “The Ituri Project” and lasted about 10 years from 1980 to 1990. The flood of interest was similar to that in the !Kung. Research was affiliated with 11 different institutions in three different countries and covered everything from nutrition to genetics to child development. The most notable of these, for our purposes anyway, was Edward Tronick, a professor from the Department of Psychology at University of Massachusetts Amherst who studied child-rearing practices among the Efe. Tronick’s research, along with that of his team (notably Steven Winn and Gilda Morelli) forms the backbone of all Efe references throughout my work, since it gives us the most detailed picture of what motherhood was actually like in Efe society. I can only imagine what the Efe must have thought of this sudden, strange fascination that white people suddenly seemed to have in the way they lived every aspect of their lives. If they found it bizarre, they were polite and cooperative, and probably received an abundance of tobacco in exchange for their troubles.

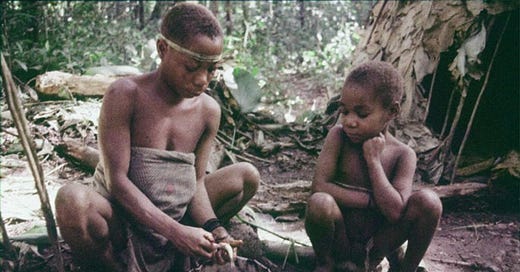

Efe woman and child in camp

Side note: actually, the exchange economy that researchers developed with the Efe appears to be even more bizarre. While the Efe were indeed given tobacco and food in exchange for their cooperation in research, anthropologists also gave them “polaroid pictures of themselves and their children in return for divulging their marital and reproductive histories” and “a small handful of salt” to anyone who allowed themselves to be measured. (Like the !Kung, the Efe are quite small. The average height for men is about 4’10” and for women 4’8”). Other gifts included plastic earrings, cheap watches, and of course, rides in the Land Rover.

Robert Bailey was to the Efe what Richard Lee was to the !Kung. He was the pioneer who set off through the jungle to find a suitable research site for all subsequent field work. In 1980, he found one. The site that Baily chose for his research was called the Walese Dese and was apparently chosen explicitly because the only road leading to it was in “such a state of disrepair that passage by commercial trucking is prohibitively risky and even small, four-wheel drive vehicles traverse it infrequently.” One can only imagine that Baily and Lee would have had many a miserable truck-repair story to share over drinks. Perhaps the Man the Hunter conference should have included some lectures on “how to drive and repair a Land Rover in extremely adverse conditions,” a skill that is seemingly required of any ambitious hunter-gatherer anthropologist. The poor condition of the road meant that the Efe and their agricultural neighbors the Lese lived mainly as a self-sufficient unit without much outside contact (although they did occasionally sell peanuts, rice, and bushmeat to brave passing truck drivers who dared take on the afore-mentioned road).

The Ituri rainforest environment is quite different from the Kalahari desert, to say the least. Whereas the Kalahari is characterized by savannah, sand and dry brush scrub, the Ituri is a full-blown tropical rainforest. Actually, scientists believe it was once much drier and may have actually been similar to the !Kung savannah environment until as recently as 3,000 years ago. Since agriculture probably arrived in the region before that time, there’s no evidence to suggest that hunter-gatherers were ever able to survive in the rainforest environment without supplementing their diets with agriculture foods. We have a stereotyped idea that rainforests are abundant places, but the Efe have a much harder time hunting and gathering compared with the !Kung, especially during the period from April-June when most of the gathered foods the Efe rely on are no longer in season.

Although when research on the !Kung first began, many were still living as true, economically-independent hunter-gatherers, the Efe had been involved in trade with their agricultural neighbors, the Lese, since long before any formal research commenced. Although they might not win the award for the most “untouched” hunter-gatherers, there are many similarities between their lifeways and those of the !Kung, despite the extreme differences in local ecology, which strengthens arguments for these being features of our shared evolutionary past. Like the !Kung, they construct temporary shelters from found natural materials and they move often (sometimes as often as every two weeks). For seven months out of the year the Efe live near the Lese Villages but for the other five months they live deeper in the forest. They live in small bands of about 20-30 people and are mainly virilocal (meaning the married couple typically lives with the husband’s family) but because of the highly fluid nature of groups, this is more a guideline than a rule. The Efe are also famous for their intensely communal child-rearing practices, with babies averaging as many as 14 different caregivers in a single day. Babies are often nursed by women other than their mother and may switch caretakers as many as eight times per hour. Data from research on the Efe presented one of the first major challenges to attachment theory being solely about the mother-infant relationship, as we will discuss often in this book.

Although I was unable to find any detailed information about the current status of the Efe, it appears that they are befalling the same fate as so many other hunter-gatherers. Commercial loggers are encroaching on their traditional lands and, because the Efe have no formal titles to their land, there is little they can do about it. Many have little choice but to engage in paid wage labor assisting the loggers. As their forest disappears, so will their hunting and gathering lifestyle.

The Efe are one of four populations collectively referred to as the BaMbuti, all of whom live in the rainforest of the Congo. Another sub-group of the BamButi is the Aka, or BaYaka, who have also been extremely well-studied, and who are the ongoing subject of some of the best research in the field today. Like the Efe, they have a similar reciprocal exchange relationship with their agricultural neighbors, the Ngandu but have nevertheless maintained much of their traditional hunting and gathering lifestyle. They do not cultivate any of their own food. They live in temporary huts and move frequently. Their diet consists of a variety of 63 kinds of gathered plants, 23 species of hunted game, as well as nuts, fruits, honey, mushrooms and roots. They trade honey and bushmeat for yams, taro, maize and other crops from the Ngandu. They are bilocal (meaning that a husband-wife pair is equally likely to live with the father’s family as with the mother’s). They are most famous for their extremely doting fathers. Aka fathers hold infants up to 43% of the time and have even been observed to suckle them (apparently milk-free male nipples still make great pacifiers). Men regularly bring infants along to bro hangouts, where they drink palm wine together and talk about manly things, all while suckling babies in slings on their chests.

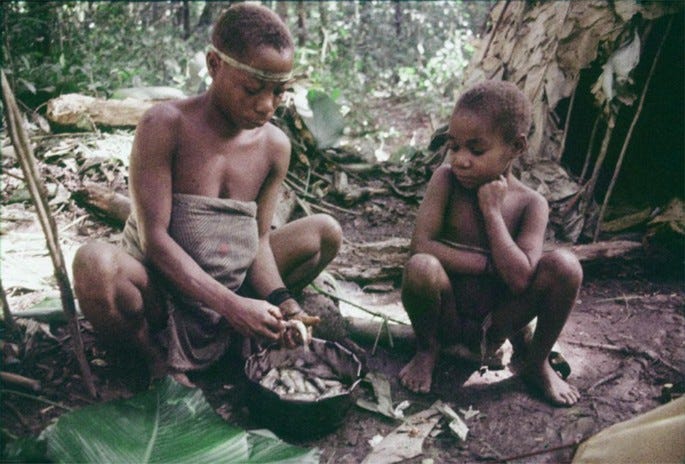

Aka fathers with their children

To my knowledge, the Aka were never subject to the same furious onslaught of research like the !Kung and the Efe. The earliest research on the Aka is in French, since from 1910 to 1940, the Aka lands were part of French Equatorial Africa. Although many affiliated tribes were forced into laboring on rubber plantations, the Aka were largely able to escape this fate by retreating deeper into the rainforest. Most of the research on the Aka included in this book comes from two researchers. The first is Barry Hewlett, who began his research with the Aka in 1973, seven years before the Ituri project on the Efe swung into full gear. Hewlett started his career working for social service and child development agencies and so he was particularly interested in Aka childrearing practices. Fortunately for us, this means he also collected a lot of data on mothers. He also produced the fascinating documentary called Caterpillar Moon about the Aka, which I highly recommend to anyone interested in learning more about them. More recently, Nikhil Chaudhary of the University of Cambridge has done a lot of interesting research on the Aka, with the aim of understanding contemporary mental illnesses from an evolutionary perspective. Dr. Chaudhary is pioneering new research in evolutionary psychiatry, attempting to understand how many common post-industrial mental illnesses may be “diseases of modernity” resulting from “evolutionary mismatch.” Needless to say, I am a fan of his work.

Today, there are very few Aka still living as hunter-gatherers. Many work on neighboring coffee plantations, while others work in the ivory and lumber trade. The World Wildlife Fund has been working to help protect the area from logging, but whether or not their efforts have significantly helped the Aka is unclear.

…

Meanwhile, over a decade before Richard Lee was busy attempting to jack his Land Rover out of the mud in the Kalahari desert, an eccentric Brit named James Woodburn was learning how to get his own Land Rover unstuck without a jack somewhere near Lake Eyasi in Tanzania. Here’s his advice:

“If you have no effective jack or the jack just sinks into the mud when you try to jack up the car, the trick is to get the spare wheel out and put it down on the ground next to one of the sunk tires. Then cut a long length of timber [assuming you have an ax handy] and insert it under the axel, using the leverage of the spare tire to lift the car. Then get some bits of wood and stone under the wheels in order to drive it out.”

Like I said, there really should have been a lecture on this at Man The Hunter.

The reason why Woodburn was driving his Land Rover around the god-forsaken mud roads of Tanzania was that he was searching for the Hadza, a notoriously shy group of hunter-gatherers reportedly living there. The Hadza live in the north of Tanzania near Lake Eyasi which is just at the edge of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (not far from where the Leakeys found the remains of Homo Habilis). The habitat is savannah woodland, though it is much more lush than the Kalahari desert (especially during the wet season from December through May). I had the privilege of doing primatology field work in this region as an undergraduate student and it is, in my humble opinion, one of the most beautiful places on earth. There are vast plains full of wild game flanked by dramatic mountains and rock formations. During the rainy season the plains are a lush green, studded with the picturesque silhouettes of Acacia and Baobob trees. When it comes to hunter-gatherer real estate, the Hadza hit the jackpot.

No one had formally studied the Hadza before Woodburn, but their existence had been documented by a German explorer in 1890 (Tanzania was a German colony from 1885 to 1918) and then by a few British colonial officers in the period from 1910 to 1940 (In 1920, the League of Nations transferred German East Africa to the United Kingdom as a mandate, and it remained under British control until its independence in 1961). The Hadza did not trust Europeans or their African neighbors and were very good at hiding from them. They had good reason to steer clear. The slave trade apparently passed within 300 kilometers of Hadza territory in the 1870s. In the 1920s, the British attempted to force the Hadza to settle down and take up farming. The Hadza had lived such an isolated existence prior to this time that they had little immunity to infectious diseases and many of them died. After only a few months, the Hadza left the settlement and returned to hide in the bush.

Subsequent encounters with neighboring pastoralists were equally unpleasant. In the 1920s, a British colonial officer by the name of Bagshaw took an interest in the Hadza and recorded a story about their one and only known experiment in pastoralism. The Hadza had apparently exchanged ivory tusks from an elephant they had killed for some goats owned by their pastoralist neighbors, but when the goats ran off into the bush, no one bothered to follow them. It turns out, following goats around all day is a lot of work, and the Hadza felt they were better off hunting and gathering, as they had always done. The goats were eventually recovered by a group of Datoga pastoralists who claimed the Hadza had stolen them and savagely killed many Hadza in retaliation. The Hadza went back into hiding and never got involved with goats again. In fact, they got so good at hiding, that many neighboring pastoralists believed that the Hadza could literally make themselves invisible. In the 1960s, after Woodburn succeeded in making a documentary about the Hadza, it was denounced by many Tanzanian viewers as a fake, because most of the Hadza’s own countrymen did not even know of their existence.

So when Wooburn started searching for the Hadza in 1958, he was having a hard time, mostly because they did not want to be found. Woodburn was a graduate student at the University of Cambridge in the department of anthropology interested in studying African hunter-gatherers. At the time, hunter-gatherer research was mostly limited to native American tribes and Australian aborigines (remember, this was before Man the Hunter and subsequent research on the !Kung and Efe societies). Wooburn had learned about the Hadza from Henry Fosbrooke, a colonial official in Tanganyika (as it was called at the time) who had trained in anthropology at Cambridge and who confirmed that the Hadza were still living as hunter-gatherers. So Woodburn, only 23 years old at the time, decided to do his graduate research on them. He had, in his own words, “zero field training” since the general view among the staff in the department of anthropology of Cambridge at the time was that “if postgraduate students were any good, they could work out for themselves what they should be doing in the field. And if they couldn’t do this, then they would fail and deserved to fail.” At the time there were no mobile phones, no portable radios, no portable tape recorders, no GPS, and no paved roads in most of the whole of Tanzania. After purchasing a Land Rover in Kampala, Woodburn drove to Mburu, a small government settlement of about 100 people which was about 20 miles from Hadzaland, where he received permission from the commissioner to enter Hadza territory. When he got there, he was greeted by a bunch of empty land, with no notion of how he would ever find the Hadza or, if he did, how he would even recognize them as Hadza, much less speak to them. In an interview recorded later in his life he recalls, “I thought I would be able to find someone who spoke both Hadza and English but of course no such person existed. No one had any idea how to find the Hadza or how to speak their language.”

He eventually made his way to Isanzu where there was a missionary outpost, hoping that they might know how to find the Hadza. The reverend, Robert Ward, was an American Lutheran missionary who had indeed made contact with the Hadza. In fact, he was very eager to convert both the Hadza and Woodburn (a non-believer) but was unsuccessful on both counts. He did, however, introduce Woodburn to two young Italians who were looking to pay their way to America by hunting a few elephants and selling the ivory. They had hired a pair of local trackers and one of the trackers was half Hadza (although he had never lived as a hunter-gatherer himself). Although the tracker spoke both fluent Hadza and fluent Swahili, unfortunately Woodburn spoke neither. Nevertheless, the tracker was hired on the spot and Woodburn got to work learning Swahili.

Woodburn's first encounter with the Hadza was after driving the Italians into the bush in search of an elephant to shoot. They were successful. About an hour after they shot it down, three Hadza men appeared from out of the thicket, apparently tipped off by the circling vultures and hoping to get some free meat. Woodburn followed them back to their camp, along with his newly-hired interpreter. He was not welcome. One older Hadza woman made a big show of telling everyone to run away (which Woodburn could not understand, but he was smart enough to get the gist). Woodburn himself felt so certain that they would indeed abandon camp that he frequently woke up in the dead of night just to check that they were still there. They later told him that they had indeed intended to run away but just hadn't gotten around to doing so. Eventually, Woodburn did earn their trust and learn their language, and so began a long string of anthropological research on the Hadza which continues to the present day.

Hadza women and children go gathering

There are so many researchers that have worked with the Hadza since Woodburn first tracked them down in the 1950s that it would be impractical to list them all here. Apart from Wooburn, the Hadza anthropologists whose research I cite most often in this book are Nicholas Blurton Jones, Frank Marlowe and Alyssa Crittendon. Blurton Jones was part of the !Kung research project in 1978 and began his research with the Hadza shortly thereafter in 1982. He was such a dedicated student of the Hadza lifeways that he conducted research with them every two years from the time he began his work in 1982 until his retirement in 2001. Frank Marlowe was introduced to the Hadza by Blurton Jones and began work with them as a grad student in 1995. Marlowe wrote The Hadza Hunter-Gatherers of Tanzania, a complete ethnography of the Hadza which I cite extensively. You will be happy to know that in it, he had the good sense to record the Hadza Land Rover song. It goes like this:

“Here we go riding in Frankie’s car, riding here and there in the car

When Frankie comes, we go riding in the car.”

It should be sung in a three-part harmony, according to his notes.

The Hadza are similar to other hunter-gatherer groups in that they are nomadic, non-territorial and egalitarian. They build temporary shelters and move often. They eat a varied diet of plants, tubers, berries and wild game. The men are excellent hunters and trackers. As Woodburn puts it, “I thought I was good at walking, until I met the Hadza.” Women possess excellent knowledge of plants and are described as “hardy.” The quality a husband values most in a wife is “hard-working,” although they don’t actually work that hard by Western standards. They raise their children collectively, although they are somewhat less indulgent than the !Kung. Like the !Kung, they speak a click language. They are bilocal (meaning there is no firm rule as to whether a husband-wife pair live with her parents or his) and camp residence is fluid. They are serially monogamous. They have rich cultural traditions and are excellent dancers and singers. As Marlowe describes it, “Their dancing is unique and full of soul - the most sensual dancing I’ve ever seen.”

The Hadza’s story is similar to all of the other’s we have heard so far. Most of the Hadza lands are now a private hunting reserve and the Hadza are prohibited from hunting there. They are restricted to a small reservation within the reserve. Because Safari tourism is so popular in the area today, the Hadza themselves have become a tourist attraction, although most of the money is siphoned off by local government and tourism companies. The money that remains is mainly used to buy alcohol and alcohol-related deaths among the Hadza have spiked. In 2007, the local government sold a huge chunk of Hadza land to a family of royals from the United Arab Emirates as a personal safari playground. Hadza resisters were imprisoned. After protests and negative international press coverage, the deal was rescinded, but it did little to slow the general encroachment that will likely eventually result in the full privatization of Hadza land.

That concludes the introduction to our African hunter-gatherer teachers, so now let’s hop on a mental airplane and fly around the world to South America, to the rainforests of Paraguay, where the Ache live…(coming next week!)

Sad. History repeats itself.