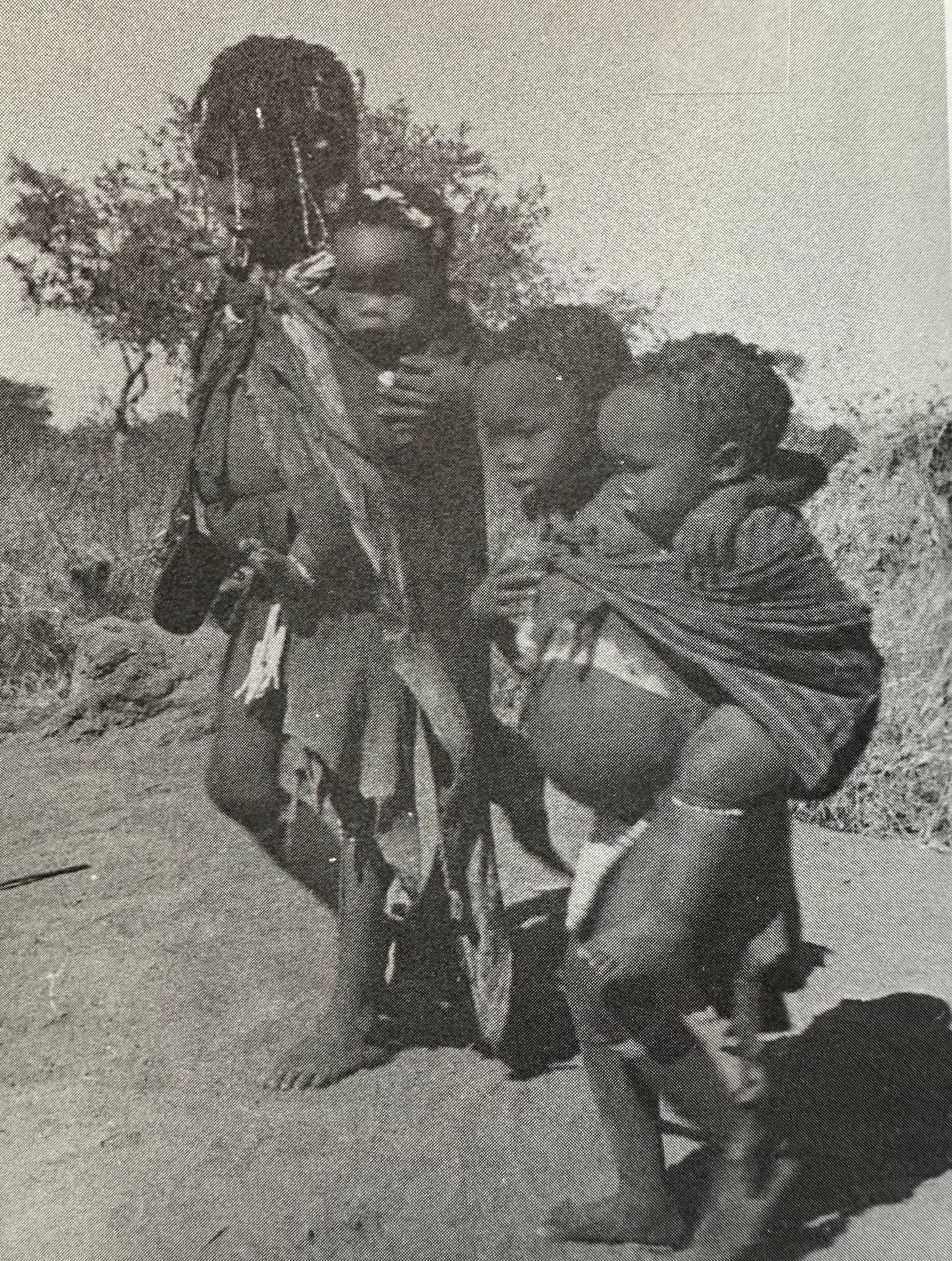

!Kung children, photo from Sarah Hrdy “Mothers and Others.” Peabody Museum, Marshall Expedition image.

In hunter gatherer societies, long before a woman has her first baby, she learns the ins and outs of parenting by observing and assisting mothers in the community. As young as the age of 3 or 4, she may begin taking on informal and unassigned care of younger siblings, cousins, or unrelated babies. This care is typically provided within the context of a multi-age playgroup where older children share responsibility for the younger children, while collectively engaging in play. Often there is a hierarchy of care in such groups, whereby the youngest children are held or cared for by slightly older children who are in turn cared for by even older children. Anthropologists have often observed an 8-year-old supervising a 4-year-old who is holding a 1-year-old. Adults are always within earshot and provide the majority of nurturance and sustenance, even if they are largely absent from children’s play and direct daytime supervision.

Care and holding is also provided by other adult and subadult maternal helpers outside of the context of the playgroup, and care within playgroups is provided by children of both genders, but in most hunter gatherer societies the most present and helpful caregivers are young girls between the ages of 8 and 12. There is a passage from Melvin Konner’s ethnographic research on the !Kung that beautifully illustrates how communal child-rearing is in these societies, and how eager girls are to help and interact with babies:

“From the baby’s position on the mother’s hip they have available to them her entire social world…When the mother is standing, the infant’s face is just at eye-level of desperately maternal 10-to-12-year-old girls who frequently approach and initiate brief, intense, face-to-face interactions, including mutual smiling and vocalization. When not in the sling they are passed from hand to hand around a fire for similar interactions with one adult or child after another. They are kissed, sung to, bounced, entertained, encouraged, and even addressed at length in conversational tones long before they can understand words.”

Why do girls spend more time helping than boys, and why are pre-reproductive girls the most eager to help? One theory is that by helping, these girls are learning critical mothering skills that will facilitate their own transition to motherhood, usually around age 19. Contrary to what many of us believe, research suggests that many aspects of mothering are actually “learned” skills in primates, rather than hard-wired or instinctive. In free-ranging Vervet monkeys, juvenile females show a high degree of interest in caring for infants and, by the time they are subadults, this practice has made them into competent allomothers (Lancaster 1971). By contrast, many primate species raised in captivity, deprived of social learning opportunities, are incompetent mothers, and may go so far as to completely reject their offspring (Lancaster 1971). Other evidence from captive groups of vervet monkeys suggests that allomothering as a juvenile makes first-time mothers more likely to successfully rear their infant (Fairbanks 1990).

Given the importance of allomothering in non-human primates, and the relative complexity of human mothering, it is likely that humans also benefit from learning to mother through allomaternal caregiving. This kind of pre-reproductive “mothering practice” is something we have largely lost sight of in contemporary post-industrial societies, where we spend relatively little time caring for babies and children before our first birth. Post-industrial demographic shifts to life in nuclear families and dispersal of kin networks has made mothers more reliant on paid help and help from partners (Spake et al 2021). At the same time, delayed onset of first pregnancy, close interbirth intervals, and norms around school participation have made care of children by children and adolescents increasingly rare (Spake et al 2021). As such, there are relatively few opportunities for sub-adult females to practice their mothering skills prior to first birth. Even when there are opportunities, cultural norms around adolescent care of babies and children has greatly reduced the likelihood that they will actively participate in caregiving activities. A U.S. nationally representative sample of households with children found that 22% of these families had adolescents (age 12-18) along with younger children (under age 12), and among those, adolescents regularly participated in childcare in only 20% of such families (Capizzano et al 2004).

Even the long-standing American tradition of teenage babysitting is on the decline. In an article published last month in the Atlantic, Rachele Daminelli writes, “babysitting used to be both a job and a rite of passage. For countless American teens, and especially teen girls, it was a tentative step toward adulthood - responsibility, but with guardrails.” She goes on, “today, the teen babysitter as we knew her has all but disappeared. People seem to worry less about adolescents and more for them, and their future prospects. There’s not much reason to fear or exalt babysitters anymore - because our society no longer trusts teens to babysit much at all.”

We will talk more about the trend towards overparenting and overprotecting children in later chapters, and the ramifications for both adult and child mental health, but for now let’s consider the impact this relative lack of experience may have on first-time mothers. If mothering is indeed a learned skill, then parenting experience prior to first birth is likely to increase a mother’s sense of self-confidence after her first child is born. Today, in contemporary post-industrial societies, mothers often rely on advice from medical professionals, parenting books, social media and childcare professionals to fill in the gap. But humans often learn best from observation and replication, and the advice in these books can feel hard to implement. Not to mention, advice from “experts” is often confusing and conflicting, leaving us to wonder what is truly the best approach.

Lack of mothering experience prior to first birth is a real issue in contemporary post-industrial societies. There is substantial evidence suggesting that maternal self-efficacy - a fancy word for self-confidence and competence in infant care - is inversely correlated with perinatal mood disorders, especially for first-time mothers. (Razurel et al 2016 and Haslam et al 2006). It seems probable that parenting experience prior to first birth is one of the best ways to increase a mother’s sense of self-efficacy, which leads me to believe the lack of “motherhood practice” is part of what sets us up for a difficult transition to motherhood in contemporary America.

I struggled with every aspect of mothering my first baby, despite having read nearly every parenting book I could get my hands on. I remember lying awake towards the end of my pregnancy, wondering about things like, “How will I know when to change the diaper? How can you tell if it’s dirty?” This particular issue turns out to be fairly obvious, but it illustrates just how little I knew about taking care of babies. Prior to the birth of my son, I had had a few babysitting gigs as a college student, mostly caring for slightly older children who were beyond the nursing and diapering phase. My younger brother was only two and half years younger than me, and there had been no baby cousins or other relatives nearby. The first night home from the hospital, I remember just staring at my baby thinking, “but what do I do with it?”

Eventually, I figured it out, as we all do, but I can’t help wondering, would more baby-caring experience earlier in life have helped buffer me against some of the struggles I experienced in my oldest son’s first year? What do you think? Did you have any care experience prior to your first birth? Would more experience have helped?

I’m the eldest of four total, 3 younger brothers. I’m proud to say I was their second Mom. And I certainly wouldn’t be the kind of Mom I am today if it wasn’t for them.

Kids need responsibilities and jobs in the family, no matter what their birth order is. It’s part of life. Otherwise we are just raising kids in prolonged childhood/adolescence.

I'm the eldest of nine and we were all homeschooled until I was nearly in high school. Literally the only skill I really had to learn once I had my own babies was nursing.