Introducing the hunter gatherers (and the crazy anthropologists who study them), Part 3

In which we meet the Ache and the Agta

In my last two posts, we wrapped up our introduction to the African hunter-gatherers (you can catch those here and here if you missed them), so now let’s hop on a mental airplane and fly around the world to South America, to the rainforests of Paraguay, where the Ache live. I tried to find some amusing anecdotes for you about Ache anthropology, but it turns out there is absolutely nothing humorous about the Ache history or the people who study them. From the first recorded contact with the Ache in the 1600s, their history is one of abuse, enslavement, and massacre by colonial forces. In the 20th century, when Paraguay was under the rule of military dictator Alfredo Stroessner, the Northern Ache, who had previously occupied nearly 20,000 kilometers of ancestral territory, were forced onto a reservation of 50 square kilometers. One particularly corrupt official by the name Manuel Pereira was in charge of rounding up the Ache and had a salary directly tied to how many “indians” he could bring under his control. He also embezzled most of the limited resources that were earmarked for the Ache in order to fund his drinking problem. There is some controversy as to the extent to which armed force was used to corral the Ache into the reservations, but whether via social coercion or physical deplacement, the Ache had little say in their relocation. Like the !Kung and the Hadza, many suffered and died from tuberculosis and respiratory illnesses to which they had no immunity while living on the reservations. Their land was given over to large, multinational business groups who sold them to foreign investors for development. The “pacification,” as it was called, of the Ache people during this time was so destructive that the Ache presented a formal complaint of genocide.

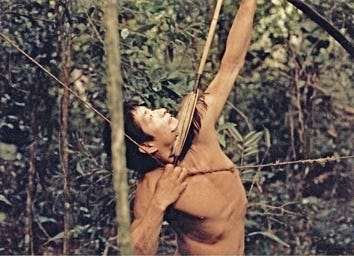

An Ache man hunts

Although there are descriptions of the Ache going as far back as the 1600s, they were not formally studied until the 1970s, just as the hey-day of !Kung research in Botswana was coming to an end. Most of the anthropological work on the Ache comes from yet another husband-and-wife team, Kim Hill and Magdalena Hurtado. Kim was a disillusioned molecular biology graduate student who decided to quit his PHD and sign up for the Peace Corps as a volunteer in Paraguay, where he first encountered the Ache. Upon returning, he decided to re-enroll in grad school for anthropology, despite advice from Harvard University Anthropology Professor Maubury-Lewis that, “only people who want it more than anything in the world should consider anthropology as a career.” His wife, Magdalena Hurtado, was a Venezuelan student who had come to the United States to train in anthropology in order to better assist Venezuelan indigenous groups, but ended up mostly researching the Ache with her husband. By the time their research began, the Ache had been “settled” into five major Catholic mission reservations and only about 20-25% of their diet was from hunting and gathering. Nevertheless, the Ache continued to hunt and forage in the forest, sometimes for weeks or months at a time, and based on observation of their life during these forest visits, Hill and Hurtado were able to reconstruct much of what their ancestral lifeway must have been like.

Compared to the !Kung, the Ache work hard for their calories. Men spend a rigorous seven hours a day hunting and women spend most of their waking hours in gathering, food processing and childcare. The Ache are unusual in that the men provide the vast majority of the calories - 87% - and their diet is mostly meat: armadillo, monkey, and various kinds of deer. I can’t help but suspect that the disproportionate reliance on meat and the strenuous effort required to hunt it may be the result of environmental destruction by loggers, since similar transitions have been documented in other societies. I have no data to back me up on this, but I would not be surprised if women’s gathering work represented a higher share of calories in their past, as is the case with other groups living in more pristine environments with less outside contact. While in the forest, the Ache build temporary shelters and move often in small, fluid groups of about 10 people. Individuals choose their own marriage partners and apparently they are not very good at it. Divorce is quite common and, according to Hill and Hurtado, post-reproductive Ache women report an average of twelve mariages over the course of their reproductive lives! Most women produce children with up to five different partners. As in other hunter-gatherer societies, polygamy is rare, so despite the high number of sexual partners, they prefer to have them one at a time. Like other hunter-gatherers, they are intensely egalitarian, share everything, and frequently express affection through physical contact.

Side note: Kim Hill has been embroiled in some interesting controversies regarding uncontacted Amazonian tribes. In a 2015 article printed in Science, Hill and another anthropologist, Robert Walker, advocate for controlled peaceful contact with uncontacted tribes, stating that isolation leaves them vulnerable to unplanned contact from miners, loggers and hunters. Hill cites evidence that during planned contact with the Ache in the 1970s, he and others were able to provide medical care and nutrition to groups in transition, thereby preventing them from befalling the fate of earlier “pacification” attempts. In response, Survival International, a human-rights NGO based in London whose goal is to help indigenous people keep their ancestral lands, wrote an open letter urging the anthropologists to retract their statement, saying that “the proposal is both dangerous and illegal, and undermines the rights that Indigenous peoples have fought long and hard for.” Hill is also controversial for his association with Professor Napoleon Chagnon, whose research focused on violence among the Yanamamo tribe in the Amazon. Chagnon is famous for arguing that this kind of cultural violence is a product of natural selection because violent men leave more offspring. Both his conclusions and his methods have been roundly accused by others in the anthropological community, who argue that the rates of violence were overstated and were largely the result of social change following contact with colonial forces. Indeed, violence is observed to increase markedly in most hunter-gatherer societies after they “settle,” gain access to alcohol, and money or wealth from wage labor. Furthermore, the American Anthropological Association also found that Chagnon was in violation of multiple codes of ethics in his research of the Yanamo. Marshall Sahlins, world-famous anthropologist and author of Stone-Age Economics who called the !Kung “the original affluent people” was one of Chagnon’s graduate teachers but apparently disliked him so much that he resigned from the National Academy of Sciences when Chagnon was appointed a member. Sahlins and others claimed that Changon had actually paid the Yanomamo in machetes, axes and guns for participation in his research, thereby escalating the violence he sought to study. Chagnon has since been barred from anthropological research in Venezuela (where the Yanomamo live). Much of the controversy was kicked off by the publication of a book called Darkness in El Dorado by Patrick Tierney. In the aftermath of its release, Hill felt compelled to issue a statement saying that he had “not unconditionally defended Napoleon Chagnon,” although he was clearly a fan. I do not mean to throw Kim Hill under the bus. The research he did with Hurtado on the Ache was interesting and important (and seems to have been done ethically) but these controversies illustrate some of the real ethical challenges of anthropological field work and the impact that anthropologists have had on isolated hunter-gatherers.

Last but not least are the Agta of the Northern Philippines. I always remember the Agta by the fact that the women are hunters! They hunt almost as much meat as the men do and are able to do so while carrying babies on their backs. When this observation was first announced by the husband-wife anthropology team Griffin and Griffin, it was met with much skepticism. Fortunately, yet another husband and wife anthropology team, Headland and Headland, were able to confirm it. Thomas Headland wrote on his blog:

“Agta are most widely known by anthropologists today because of the Griffins' articles claiming that some Agta women hunt large game with bow and arrow. Being the skeptics that we are, we didn't believe this when the Griffins first described it in 1978. However, in a trip through the Griffins' research area…in April 1979, I found Agta bands where the women did hunt pig and deer with bow and arrow…I still found it hard to believe, so I asked [a woman] if she could demonstrate her skill by shooting at a nearby banana plant. She readily did this with ease, burying an arrow into the center of the trunk from 30 feet away.”

Ha! Take that skeptics! More recent research has emphasized the fact that the women no longer hunt, but since hunting has declined to only 5% of subsistence activity at the time of this later research (having been replaced by agriculture and wage labor) this hardly seems to refute earlier claims that they once did. Nevertheless, I feel compelled to say that they are the exception and not the norm. Across hundreds of hunter-gatherer societies studied by anthropologists, women mostly gather and men mostly hunt. As Robert Kelly puts it in his seminal work, The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers, “the division of labor is rooted in fundamental biological differences between men and women and the incompatibility of children with hunting.” This may be an unpopular and controversial thing to say these days, but it’s what the data supports. If you watch John Marshall’s documentary The Hunters, in which a group of !Kung men take down a giraffe, it will be obvious to you why this is not an activity compatible with pregnancy and breastfeeding (and most hunter-gatherer women spend the majority of their adult lives in one of those two states). I deeply appreciate the data we have on Agta women hunters because it’s proof that women are fully capable of hunting, and even of taking down large game in certain contexts, but it’s simply not an optimal survival strategy in most hunter-gatherer societies.

Agta people hold up a giant snake skin with Thomas Headland and son

The Agta live in the rugged Sierra Madre mountains on the east coast of the main island in the Philippines. The habitat is characterized as semi-seasonal tropical rainforest. Like so many other hunter-gatherers discussed above, the Agta rely on trade with their agricultural neighbors for the bulk of their plant food, which they trade for wild game (although recently they have switched to spear-fishing and intertidal foraging since terrestrial game has disappeared). They are semi-nomadic and live in small, mobile groups of about 50 people. Residence patterns are bilocal and fluid. The Griffins described them as having “profound gender egalitarianism,” which stands in stark contrast with surrounding Filipino society where women are subordinate and public life is reserved for men. They are mostly monogamous and rear their children communally, just like every other society described in this chapter.

What has recent history been like for the Agta? You guessed it: exploitation, land loss, and increasing dependence on agricultural neighbors. They were raided by slavers before Spanish colonialism and were subsequently recruited to fight in the guerilla and military forces. Since the 1950s, Agta independence has steadily eroded as their traditional lands have been massively deforested by loggers with disastrous consequences for the local ecosystem, rendering the continuance of their hunting and gathering lifestyle nearly impossible. They have dabbled in agriculture - manioc, sweet potato, rice - but their farmland and crops are often stolen by aggressive non-Agta neighbors. Serious settlement attempts have been underway since the early 70s but some Agta have managed to resist. They are still currently embroiled in battles for rights to their ancestral lands.

The Griffin family (father, mother and son) were the first to formally study the Agta, but they have been the subject of ongoing research by many anthropologists and are still actively studied today. Although much of their traditional lifestyle has been disrupted, research on the Agta and the BaYaka (discussed above) has yielded some fascinating papers on everything from gender egalitarianism to communal child rearing to multi-age playgroups, much of which is cited in my work. Perhaps the most interesting anthropologists to study the Agta were Thomas and Janet Headland, who moved in with the Agta in 1962 and stayed there for 24 years, raising their three children alongside the Agta in the jungle. “They grew up bilingual and bicultural,” say the Headlands on their blog. “While some may think this way of life must have been a trial for us or our children, the five of us think otherwise.” The Headlands go on to describe a romantic life of fishing, swimming, and exploring the rainforest with their Agta friends, and only briefly mention that swaths of them were simultaneously dying of tuberculosis, which frankly seems less-than-idyllic. “The majority of [our children’s] Agta playmates today are dead,” they note, adding that all three children returned to the United States for college.

That’s it for the tour de force of our hunter gatherer teachers. It’s a lot to remember, so I’ve made you a cheat sheet you can refer back to you as we continue to explore the research (you’re welcome):

!Kung: also known as the Ju/ʼhoansi. San bushman of the Kalahari desert. Think “poster child” for hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The subject of a massive Harvard research project kicked off by Irven Devore and Richard Lee. Featured in The Gods Must be Crazy. Research on child development by Melvin Konner. Women’s stories by Marjorie Shostack.

The Efe: a group of hunter-gatherers in the Ituri rainforest of the Congo. Also the subject of a major Harvard-led research project in the 1980s. Exchange hunted game for crops with their agricultural neighbors the Lese. Famous for having extremely communal childcare (14 different caretakers for one baby in a day). Research on child development by Edward Tronick.

The Aka: another group of hunter-gatherers living in the Congolese rainforest. They also have an exchange relationship with their agricultural neighbors. Famous for having extremely affectionate dads (who do a lot of infant care). Still the subject of ongoing anthropological research today. Studied extensively by Barry Hewlett.

The Hadza: a picture-perfect group of hunter-gatherers living in the savannah environment near Lake Eyasi and the Ngorongoro crater in Tanzania. Famous for being “shy” and expertly evading colonial intruders. First made famous by James Woodburn and subsequently studied by a whole string of anthropologists, including Frank Marlowe who wrote their ethnography. Still the subject of ongoing research today.

The Ache: a group of hunter-gatherers living in the rainforest of Paraguay. They have an especially tragic history and today are mostly settled on a mission reservation, although they still spend months at a time in the forest. Studied by husband-and-wife team Hill and Hurtado.

The Agta: a group of hunter-gatherers living in the forest of the Sierra Madre mountains in the Philippines. Famous for women hunting big game with bow and arrow (with babies on their backs). Studied by the Griffin family and the Headland family. Still the subject of ongoing research.